Mary had well-controlled type 2 diabetes treated with nutrition, exercise, metformin, Jardiance, and Lantus insulin. One day recently, when she developed low blood glucose (hypoglycemia) a few hours after exercising, she wasn’t surprised. She had experienced lows in the past and was familiar with how they felt. She had a glass of Coke and soon thereafter she (and her blood glucose) were back to normal.

Bob, a man in his thirties with type 1 diabetes, checked his blood glucose, found it to be 80 (mg/dL), and got into his car to drive to work. A half hour later, a police officer spotted Bob’s car stopped at a green light and found him passed out at the wheel. The officer noticed Bob’s medical alert bracelet with the word ‘diabetes’ engraved on it and called for a paramedic. The paramedic checked Bob’s blood glucose. It was 50. He gave him an injection of glucagon and by the time they reached the ER Bob was starting to come around. A half hour later he felt back to his normal self. Except that his driver’s license was then suspended, he was mortified for months thereafter that he had come so close to causing a potentially disastrous car accident, and his family was terrified that he would experience another severe low in the future.

At some point, possibly in the not-too-distant future, the use of new and emerging technologies and therapies will make hypoglycemia in people living with insulin-treated diabetes a thing of the past, and incidents similar to that which happened to Mary and Bob will never happen again. But we aren’t quite there yet, so it is critical that you know about – and use – those (excellent, but not perfect) measures we do currently have to reduce your risk of hypoglycemia. And it is equally important that you and your loved ones know how to treat hypoglycemia when it does occur.

What Is Hypoglycemia?

Hypoglycemia is typically defined as a blood glucose less than 72 mg/dL (4.0 mmol/L). Insulin therapy is the most common cause, but it can also occur if you are taking medications called sulfonylureas (like glyburide). In this article I discuss hypoglycemia only in the context of insulin therapy.

What Are Symptoms of Hypoglycemia?

There are two groups of symptoms caused by hypoglycemia. There are – nerd medical terminology alert! – “autonomic” symptoms and there are “neuroglycopenic” symptoms. Okay, so you can now forget those terms. What is worth remembering, however, is that some symptoms (the autonomic ones) like shaking, heart pounding, sweating, and feeling anxious are your best friends because they alert you to the fact that something is wrong so you can take action before your blood glucose gets so low it becomes a worsening threat. If your blood glucose gets down below 54 mg/dL (or so) you can develop dangerous (neuroglycopenic) symptoms of impaired thinking, confusion, drowsiness, and even loss of consciousness (as Bob had in the anecdote above).

How Is Hypoglycemia Classified and Why Should I Care?

Doctors typically refer to episodes of hypoglycemia in terms of whether or not they are “severe.” When doctors refer to severe hypoglycemia they are referring to hypoglycemia that is so bad you need someone to assist or even rescue you, as you are so incapacitated by your low that you are unable to treat it yourself. Why should you care about how doctors classify hypoglycemia? You should care because if you have a low that makes you feel really, really crummy, but you are able to self-manage it (by getting some pop or honey or whatever) yet you refer to it as “severe” when you tell your doctor about it, they may misinterpret it and give you bad advice. For example, say you had a low blood glucose of 65 mg/dL and you felt crummy but were otherwise fine, yet you described it as “severe” (because it had made you feel so yucky) when you met with your doctor…

You: “Doc, I had a really severe low a few days ago.”

Your doctor: “Oh, that’s terrible. Okay, so we need to reduce your insulin doses, we need to let your glucose levels run higher than usual, and, oh, sorry, but I’m obliged to notify the regulatory authorities that you should not be driving until we’re sure this doesn’t happen again.”

Take away message: Make sure you are careful with your choice of words when describing your episodes of hypoglycemia. “Severe” to you may not be “severe” to your physician.

When I Wake Up High in the Morning It Could Be a Rebound from Sleeping through a Low Overnight, Right?

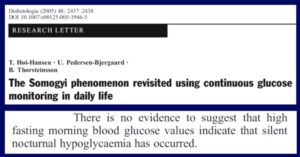

Wrong!! This is a myth that refuses to go away. “Rebounding” refers to having a high blood glucose in the morning after sleeping through a low blood glucose overnight (the so-called Somogyi phenomenon). Except the existence of rebounding was disproven over 30 years ago! (Or, if it exists at all, it must be exceedingly rare.) Nonetheless, its existence continues to be taught by well-intentioned and otherwise super knowledgeable endocrinologists and diabetes educators. If you wake up high in the morning it is almost certainly because your glucose levels were creeping up for hours beforehand (due to insufficient insulin in your body), not because you had too much insulin in your body leading to a low that you slept through. Now you know. (And if your endo doesn’t know feel free to teach them….and if they don’t believe you, here is the reference for a journal article that discusses it: Diabetologia, 2005, 48: 2437-2438). Even better, here is a screen capture of the title page of the article and its key take away message:

How Do I Avoid Having Hypoglycemia?

There are a number of strategies you can use to avoid hypoglycemia, including modifying your food intake and adjusting your insulin doses (especially in the setting of exercise. A really helpful web site is www.excarbs.com). Speak to your endocrinologist and diabetes educators to find the strategy that will work best for you. But, and this is a very big but, there is no way, if you are on insulin, that you can eliminate the risk that you will have an episode of hypoglycemia. For that reason almost everyone who is on insulin therapy would benefit from using real-time continuous glucose monitoring (using either a Dexcom, Medtronic, or Senseonics device) or, at the very least, flash monitoring using an Abbott Freestyle Libre. Real-time continuous glucose monitoring (“CGM”) or flash monitoring will help you not only avoid hypoglycemia, it will also help you achieve a lower A1c, have fewer highs, and have less glucose variability (glucose fluctuation).

Real-time continuous glucose monitoring allows you to always know your glucose level. No more guessing! And it has alarms, too, so that if your glucose level falls below a certain threshold (that you can set) it will alert you to the fact that you are either about to go low or are low (depending on at what glucose level you set the alarm). Flash monitoring, like real-time continuous glucose monitoring, also provides you with your glucose level and trending arrows so you can see if your glucose level is on the way up, is steady, or is on the way down, but the current product (the Libre) does not have alarms. A newer version (the Libre 2), now available in some European countries and hopefully available soon in North America, will have alarms.

The safest way to avoid hypoglycemia using currently available technologies is to couple real-time continuous glucose monitoring with an insulin pump that has an onboard “algorithm” (basically a pump with a brain). These “hybrid closed-loop” systems automatically adjust how much insulin they are delivering based on your glucose levels and whether your levels are going up or down. If you’re heading for a low, the pump will automatically reduce how much insulin it is giving you and, typically, prevents the low altogether (or, at the very least, makes lows far less common – especially overnight). The only FDA-approved such device is the Medtronic 670G, but likely soon also available will be the Tandem t:slim Control-IQ which will also have these capabilities. Also available are “Do It Yourself” versions which are not FDA-approved. Using these devices is called “looping.” The most popular of these uses what is called the RileyLink. You can learn about looping by typing “diabetes looping” into Google.

Fingerprick measurements, although still very commonly used and often providing very helpful information, will eventually become a thing of the past for insulin-using people as these newer technologies take over.

I’m Having a Low; How Should I Treat It?

If you have an episode of hypoglycemia that you can self-treat (that is, it is not bad enough that someone else has to assist you), you should consume 15 grams of fast-acting carbs. Choices include 6 Lifesavers, 6 ounces of soda (not diet soda!), or dextrose (glucose) tablets (the number of tablets to be taken depends on how many grams of dextrose each tablet contains). Six ounces of milk or juice will also work, but contrary to what most people think (and do) these choices work less quickly. After ingesting 15 grams of carbs you should then wait 15 minutes before you ingest any more carbs. You have to give it some time for the carbs you just ingested to work! But this is much, much easier said than done and almost everyone at times over treats a low because it feels so awful to be low! (The problem with over-treating a low is that you end up high afterward…something you likely already know from experience. So frustrating when that happens!)

If I Have a Severe Low, What Should My Loved One (or some other trusted person) Do to Help Me?

Rule number one: If you have a low bad enough that you are not able to swallow (for example, if you are unconscious or nearly so) people should NOT put anything in your mouth because you could choke on it making a bad situation that much worse! If you are confused, but awake and can safely swallow then sure, someone can bring over some fast-acting carbs (see above) and hand them to you. But if you’re in a worse situation, the person trying to help you should, if they know how to do it, give you an injection of glucagon. Glucagon emergency kits (made by both Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk) have been around for decades, but are somewhat tricky to administer as they require mixing a sterile solution and a powder together and then injecting it into your muscle (such as the thigh muscle). And all this is to be carefully done as you, someone they love and care about, are in a desperate situation. That is one tough thing to do!

Thankfully there is now newly available a premixed form of glucagon called Baqsimi (created by a company called Locemia and being marketed by Eli Lilly) which comes in the form of a nose spray. No need to mix it with a liquid. No shaking. No refrigeration. No injection. Just put the nozzle into a nostril and spray. Wow, so much better than the old way of giving glucagon! The other forthcoming easy-to-use version of glucagon, from a company called Xeris, is given with a device called a Gvoke HypoPen. The HypoPen works something like an Epi-Pen with which you may be familiar. Basically, it is an auto-injector and the person trying to assist you would hold it against a large muscle such as a thigh muscle, and the injector’s needle would automatically insert itself (and then retract back into the device) and give you the glucagon. And like Baqsimi, there is no mixing and no refrigeration required. The HypoPen received FDA approval mid-September 2019 and will be available in two doses: an adult dose and a smaller dose for children.

Moral of the Story

Hypoglycemia is never pleasant and, at its worst, can be life-threatening. Fortunately, there are highly effective ways to avoid hypoglycemia and, in the most catastrophic situations, there are now far better ways to treat it. And, excitingly, new and emerging technologies will eventually make hypoglycemia a thing of the past.

Thanks for this article. I was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, 4 months ago (in my 60’s). I have been low about three times. This is one effect of diabetes that concerns me.

Fears of hypoglycemia are very common. Here are a few other resources that may be able to help alleviate your concerns:

https://tcoyd.org/2019/08/im-so-afraid-of-going-low-i-let-my-blood-sugars-run-high-how-can-i-get-over-this-fear/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bj1-5hDA2tk&t=16s

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sMKup_cz7gU

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hzlGXPzDwvI