I attended a workshop moderated by Dr. William Polonsky, a diabetes psychologist, and Dr. Steven Edelman, an endocrinologist, that brought together both medical providers and people living with diabetes. A large sign outside the conference room read “Patients Vs. Providers,” evoking the image of a championship bout. However, this boxing match was exceedingly one-sided.

The workshop began by asking people with diabetes to describe what providers get wrong about them. Interestingly, most of them were reluctant to speak out, and complaints were at first limited to perceived violations of personal rights. Examples were given of providers performing invasive physical exams without asking permission, or describing what they were planning to do and why. After some encouragement to speak candidly in the presence of providers, certain themes emerged on the patient side, such as providers “not listening to me,” being “intimidating” or “indifferent,” having “not enough time for me,” and offering “inadequate care.”

When it was the providers’ turn to offer feedback, the complaints flowed quickly and were voluminous by comparison. They spoke of their frustration that “patients did not follow instructions”, “did not fill prescriptions for or take their medications”, and “did not bring their medications or devices to each session even though they were explicitly told to do so”. They also complained that patients were often “not honest” about how they were managing their diabetes, or that they seemed “lazy” or “too busy with other things” to devote enough time to their healthcare needs. The prevailing theme was that people with diabetes did not seem to take their condition seriously, or care as much about their health as their providers did.

The workshop ended with a search for common ground in the different frustrations and complaints from patients and providers. One conclusion was that when providers focus on what patients aren’t doing right, patients may in turn perceive a form of judgment. When the patient experiences this, it can bring a fear of being honest with their provider. A power differential is implicit in the patient-provider relationship, with the patient being labeled as the “good diabetic,” or the “bad diabetic.” This is language that I have even heard used by diabetes treatment providers toward me, and it presents challenges in developing a successful rapport. But there is hope to bridge the patient-provider gap. Before I share ideas for solutions, I’d like to ask you to reflect on this quote attributed to Albert Einstein:

“Peace cannot be kept by force; it can only be achieved by understanding.”

So how can we cultivate a climate of trust, understanding and teamwork in the age of managed care?

When we start with the premise that many problems in medical care and self-care arise from miscommunication and/or misunderstanding, patients and providers can move toward becoming partners.

Here are a few ways patients can become partners in their care:

1. Assume that your provider cares about you and your well-being.

Empathize with your provider. They juggle a daunting caseload, overwhelming documentation requirements, and often have difficulty obtaining records from your other providers. And they may not have had time to eat or go to the bathroom all day.

2. Show off your diabetes management skills.

Your provider needs as much information as possible in order to make an informed assessment and suggest corrections. They’ll need your blood sugar readings, what you eat and when, when and how much you exercise, and how and when you take your medications. If you take insulin, they need to know if you have adjusted your dosages or insulin pump settings. This is your time to show your doctor what you do every day to take care of yourself and how real the struggle can be. Make sure to bring all your medications in their bottles and all your devices including blood sugar meters, insulin pumps, smart insulin pens, apps that you use to track diabetes-related information and your continuous glucose monitor if you have one.

Leading up to the appointment, learn how you respond to food, medications, and different types of exercise. This information is invaluable! You know yourself better than anyone else. I like to tell people that I’m working on perfecting my mind-reading abilities, but until I get there, I need your help in knowing your experiences.

3. Educate yourself on your diagnosis, preferably from reputable sources, such as Taking Control Of Your Diabetes.

Attend a conference. Get to know others with diabetes and compare notes. Check out the TCOYD website, which is full of helpful articles. https://tcoyd.org/

4. Bring a list of questions to each appointment, and make sure that they are answered to your satisfaction.

5. Be real!

Tell your provider if you don’t know something or don’t understand their directions and voice your disagreement if you know their recommendations do not work for you. If you cannot afford a medicine or there is another barrier in your life that prevents you from being able to follow your doctor’s recommendation, let them know. They want to help make your diabetes self-care work with your life. For Example, if one day your child was sick, and you forgot to take your morning insulin or another medication, let them know. It’s okay. This is real life. It happens!

6. Take notes during your appointments.

It’s easy to forget all the things your provider says during an appointment, and this will help you with step # 2…becoming a diabetes self-management expert and showing off your mad organizational skills!

7. Contact your provider in-between sessions if you have a question, or a problem with your blood sugar or a medication.

Find out how your provider prefers to communicate, such as phone, email, or online patient portal. This shows your provider that you care about managing your diabetes, and using your provider’s preferred mode of communication may offer a quicker response time.

8. Seek support from your family, friends, and others with diabetes.

Attending a TCOYD conference can open your eyes to how other people with diabetes have similar challenges and are all trying to find a way to make it. Bringing a family member with you to the conference also lets them in on what you are really dealing with every day and may give them ideas on how they can better support you.

Steps for providers as partners in patient care:

1. Assume your patients care about their well-being, and try to see things from their point-of-view.

Tips to help with this:

If a patient doesn’t follow-through on your recommendations, ask open-ended questions to help them explain what is holding them back. For example: “I can see that your blood sugar is higher after breakfast. Could you help me understand what the mornings are like for you?” The answers might surprise you, and at the very least your patient will be glad that you asked.

Be flexible. If a person cannot alter their routine to fit with your recommendations, how might you be able to alter your recommendations to fit with their routine? If altering the recommendation is not advantageous to their health, explain why this is, and try to problem-solve with the patient.

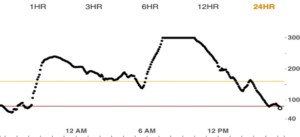

Explain why having all the data about food and insulin timing, carbohydrate intake, and exercise helps you make better decisions about their care. It may be helpful to explain exactly what you need your patients to document. Showing your patients a CGM graph like the one below without context and explaining why it poses a challenge for you to help them manage their health may offer patients an opportunity to see things from your perspective.

2. Intelligence and education level do not necessarily correspond with health literacy.

By this I mean, that your patients are trying hard, but there may be a lack of basic education on their diabetes self-management or medication management that is missing. Consider recommending conferences such as TCOYD where they can learn techniques to manage their diabetes in a supportive and collaborative environment.

Remember that your patients with T1D and insulin-dependent T2D are using calculus skills that many weren’t taught in school. And your patients with T2D may not understand why they need medications when they are barraged with messages about how diet and exercise (and cinnamon) will surely cure them.

3. Re-organize your workflow if you realize that you can’t meet the demands.

Documentation and time restrictions are major challenges to your work. What changes in your process would allow you more face-to-face time to focus on your patients, examine them, and answer their questions?

4. When in doubt, follow the “Tell Me Back” method, in which you ask the patient to describe to you what they understood your directions to be.

This will allow you to explain in a different way when something has been lost in translation. Please don’t underestimate the power of this seemingly simple intervention. It has saved me many a time. Sometimes, we don’t know that we are speaking another language, but medical terminology is not uniformly understood, and is understood differently by each patient.

5. Notice and offer positive feedback on the effort your patients are making.

Sometimes efforts don’t match results, and your patients need to know that you will continue to help them even when they don’t achieve the hoped-for outcomes.

6. Let your patients know the best way to reach you if they have a problem in between their scheduled appointments and follow-up with them in a timely manner when they contact you in-between sessions.

This lets your patients you care about their welfare.

7. If you are struggling with a certain patient, don’t be afraid to seek consultation from a peer.

An outside perspective can offer the objectivity that anyone can lose when our emotions are involved. Another approach is to imagine this patient as you would a family member for whom you care for deeply, and how you would like for a doctor to speak to your family member.

8. Consider attending a TCOYD Conference in order to learn more about how you can better partner with your patients.

In this supportive environment, sometimes patients will be more open. You may also benefit from the collegial atmosphere. Once you hear how hard it can be for people with diabetes to juggle the emotional and health challenges, you may leave with an entirely new perspective. https://tcoyd.org/

Finally, I find it helpful to remember that both patients and providers are on the same team and when we work together, it’s rewarding for everyone.

After participating in the TCOYD Conference as both a person with diabetes in 2015, and as a provider in 2019, I can attest to the quality of the programming all the way around. It is heartening to see both patients and providers in the thick of it, laughing and sharing their perspectives. I write this with gratitude for Dr. Steven Edelman and Dr. William Polonsky for creating TCOYD and the TCOYD Conference as a way to bring us all together.

These are all excellent suggestions but I (as a DCES) am disappointed that “consultation with a Diabetes Educator” is not included in the recommendations for either the patients or the providers. We are uniquely qualified to not only provide reliable education on diabetes management but to also have the time and expertise to explain everything in terms the patient can understand at whatever learning level they need.

I can’t tell you how many of my clients have expressed frustration/ anger that they had to struggle with DM management for years before finding out (oftentimes from someone other than their provider) that DM education was even available to them. I very often have had to talk them ‘off the ledge’ so to speak from changing to a new provider as a result… unfortunately, my argument is that the grass isn’t always greener… and instead encouraged them to tell their provider of their positive experience with me so they might inform more of their struggling patients of the services available to them.

You are absolutely right Cynthia! Diabetes Care & Education Specialists are an invaluable resource for people with diabetes. We do have a wonderful article on our blog about the benefits of working with a diabetes educator (https://tcoyd.org/2019/10/10-reasons-why-you-should-know-about-certified-diabetes-educators-and-how-to-find-one/) but we will continue to spread the word in as many ways as we can!